Air quality is a top concern for those in wildfire smoke-affected regions, as there are possible health effects of inhaling smoke. What are the short and long-term effects of wildfire smoke on your health? How do those health effects interact with conditions like asthma or allergies? We can answer these questions by looking closely at what wood smoke is made of and analyzing the medical research. That will help us better understand what precautions we need to take when the smell of burning wood is in the air.

What is in wildfire smoke?

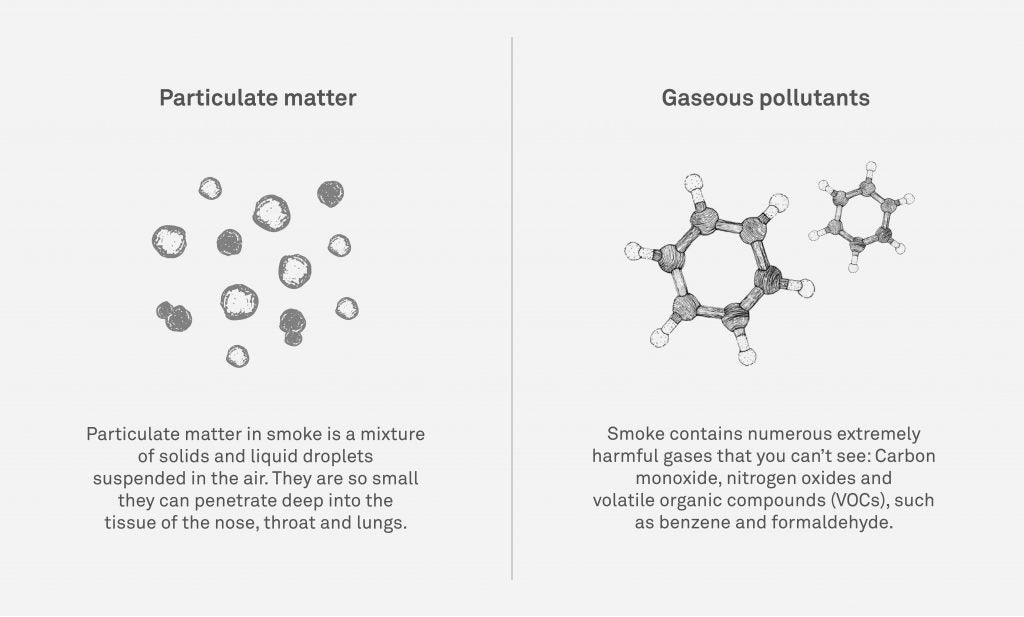

The composition of wildfire smoke is very complex. It consists of two main components: particulate matter and gaseous pollutants.

Image text: Particulate matter: Particulate mater in smoke is a mixture of solids and liquid droplets suspended in the air. They are so small they can penetrate deep into the tissue of the nose, throat and lungs. Gaseous pollutants: Smoke contains numerous extremely harmful gases that you can't see: Carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as benzene and formaldehyde.

The types of gaseous pollutants in wildfire smoke

The gaseous component can vary widely based on what type of material is burning and whether it is a wet or dry season. Though most uncontrolled wildfires happen during the dry season, there are controlled and agricultural burns that can involve wet, “green” vegetation. Severe wildfires might incinerate human-made structures adding a mix of chemical compounds from burning cars, homes and other objects in with the smoke. However, such a vast amount of wood and grass is burned by wildfires that human-made objects that burn only produce a relatively insignificant amount of chemicals. Unless you are directly downwind from a burning car, the wood smoke is the most concerning. The predominant chemical component of wood smoke is polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH). Other types of harmful gases include volatile organic compounds (VOCs), nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide.

Particulate matter in wildfire smoke: size and health effects

The particulate component of wood smoke is made up of particles of varying sizes, based on the material being burned and the temperature it burned at. Wildfires introduce a massive amount of particulate pollutants into the air, estimated to be more than urban pollution (Black et al., 2017).

The size of the particles is important because smaller particles stay in the air longer, and therefore are dispersed over longer distances and wider areas. Fine (under 2.5 microns) and ultrafine (under 1 micron) particles are of special concern, because particles that small can enter the lungs and become lodged in the tissue there, causing damage to the surrounding cells. You may see particles of this size referred to as PM2.5, meaning they are 2.5 microns in size or smaller.

When particles this small enter the lungs, they cause an inflammatory response that can extend from the surrounding cells to systemic inflammation. The damage caused by particles in the lungs can lead to greater susceptibility to infections.

Does wildfire smoke cause allergy and asthma symptoms?

Inhaling wildfire smoke has several short-term effects. The severity of these effects depends on whether or not you are at elevated risk. People at elevated risk include children, the elderly and anyone with a cardiopulmonary or respiratory illness, including asthma and allergies.

The immediate short-term effects, regardless of sensitivity, are burning eyes, nose and throat, watery eyes, runny nose, coughing and shortness of breath. Your body may produce extra phlegm in response to inhaling smoke. These symptoms are, in part, your body attempting to expel particles by washing them away. In addition, phlegm traps particles before they can reach your lungs. Even healthy adults may experience an inflammatory response of wheezing or restricted breathing.

People with asthma may have breathing difficulties in every day air. According to the EPA, the irritation caused by inhaling smoke can trigger asthma symptoms, including shortness of breath, constricted chest, wheezing, inability to draw deep breaths and chest pain.

People with allergies may have an allergic reaction to something in the wood smoke. However, the symptoms of an allergic reaction are virtually identical to the other short-term symptoms of inhaling smoke. Those symptoms may be worse than they would be for someone without allergies. Repeated exposures to wood smoke have been found to cause an allergic sensitization of the respiratory system. However, this is more likely in someone like a firefighter who battles wildfires than someone who experiences wildfire smoke infrequently (Gianniou et al., 2018).

If you are older or have a cardiopulmonary disease, asthma and allergies are the least of your worries when it comes to inhaling wildfire smoke. Particulate pollutants in smoke are known to cause an increase in heart attacks, strokes and blood clots (Wettstein et al., 2018).

There is some good news when it comes to wildfire smoke. Healthy people seem to recover fully from short-term (one hour to 24 hours) exposure, with no long-term effects, according to UCSF researchers. While short-term exposures do cause lung damage, the body heals similarly to recovering from pneumonia. However, this comes with a caveat: it is extremely difficult to study long-term exposure. There is a lot we don’t know about how long-term, repeated exposure to wood smoke affects healthy adults. Furthermore, children who are exposed to wildfire smoke can develop respiratory diseases such as asthma as a result, or they may suffer from lung development problems if their lungs are damaged while they’re still growing and developing (Sen, 2017).

How to deal with wildfire smoke if you have allergies or asthma

Allergy and asthma sufferers can take several steps to decrease the impact of wildfire smoke:

- Get away. If a major wildfire is burning in your area, and you expect the smoke to last for a full day or more, the safest course of action is to simply leave. Spend a few days somewhere without smoke.

- Check the AQI. The EPA monitors air quality across the U.S., using this Air Quality Index data to produce a map of current air quality conditions. Checking the AQI map can help you make informed decisions about wildfire pollutants in your air, which may be present even if the fire is far away.

- Limit exposure. The bulk of the wildfire pollutants will be in the air outside. Stay indoors as much as possible, and close windows and doors. This won’t keep out all of the wildfire pollutants, since your house is not air tight, but it will reduce the amount of wildfire smoke you are exposed to. Running an air purifier in the house can further reduce exposure to smoke-related pollutants.

- Limit exercise. Heavy exertion increases your breathing rate, causing more air (and more pollutants) to pass through your lungs. It also causes you to breathe through your mouth, by-passing the natural filter of your nose and nasal passages, allowing pollutants to pass more directly into your lungs.

- Wear a face mask. Inexpensive paper masks, towels and bandanas are not useful, but a properly fitted and worn N-95 or P-100 respirator mask will significantly cut down on the particulate pollutants you inhale (they are not effective against gaseous pollutants).

The combination of gaseous and particulate pollutants in wildfire smoke makes it especially difficult to deal with. The effects of inhaling particles are significantly worse if you suffer from asthma or allergies. Taking the proper steps to minimize your exposure to wildfire smoke can reduce the overall health effects on you and your family.